Blog Articles

Don’t Feed the Pigeons

by Christopher Joseph

Irrespective of whether you like pigeons or not, one thing is true – if you feed them then they quickly multiply! Just go to Trafalgar square and pull out a loaf of bread and you’ll see what I mean! The pigeon in the context of this article is of course our negative thoughts, our internal critical voice. So often in this context we ‘feed the pigeons’ by ‘beating ourselves up’ with unkind, harsh and critical comments: “Look what I’ve done now”; “Why did I do that?… you silly fool!”; “They’re going to think I’m a right idiot now!”; “Look at the state of me!”; “Oh come on – sort it out”; “I’ll never amount to anything!” etc. etc.

Irrespective of whether you like pigeons or not, one thing is true – if you feed them then they quickly multiply! Just go to Trafalgar square and pull out a loaf of bread and you’ll see what I mean! The pigeon in the context of this article is of course our negative thoughts, our internal critical voice. So often in this context we ‘feed the pigeons’ by ‘beating ourselves up’ with unkind, harsh and critical comments: “Look what I’ve done now”; “Why did I do that?… you silly fool!”; “They’re going to think I’m a right idiot now!”; “Look at the state of me!”; “Oh come on – sort it out”; “I’ll never amount to anything!” etc. etc.

The severity of the internal critic is different for different people, and varies over time for any one person, but the net effect to whatever degree is one of undermining our sense of self worth and confidence. Moreover, constant negative talk puts us in the ‘threat/defence’ mode which increases the stress hormone cortisol in our body. It is often said that if we were to speak to a friend as we speak to ourselves then they wouldn’t remain a friend for long!

But we wouldn’t speak to a friend (at least not consistently!) like this because the process of vocalising our thoughts by default brings greater awareness, care and mindfulness to what we’re saying. Therein lies the first clue as to how we can begin to change the quality of our internal voice from a cold and critical one to a kind and compassionate one – i.e. how we can stop feeding the pigeons. I’ve called this the ABC of compassionate thinking.

Awareness.

The inner critic is not something we set out to develop – it’s a habit. And, as with all habits often we run the pattern quite unconsciously, and we’re normally not even aware that we’ve been talking to ourselves in a negative way until we suddenly feel depressed, stressed or angry.

The first step to breaking any habit is awareness – awareness of the patterns that we’re currently running. Mindfulness, first and foremost, is about developing awareness, slowing down a little and coming off the ‘autopilot’ mode that we can so often live our lives on.

A short 10 minute meditation at the start and end of each day or a few 3 minute ‘breathing spaces’ practiced throughout the day can make a huge difference to our levels of self-awareness and our ability to pick up on any negative internal chatter that we might have going on!

Through developing awareness in this simple way we may begin to pick up on not only what we’re saying to ourselves internally, but the tone in which we’re saying it. Many people think that they’re internal voice is that of their mother’s, father’s or a teacher. Whilst it’s true that many people have grown up with critical teachers, parents or other family members the voice that’s currently inside our head is none other than our own! This is a good thing because it means that we’re in control – we can change it.

Breaking the pattern with kindness.

If, instead of having someone criticise us when things are hard and we’re struggling, there was someone who cares about you, understands your difficulties, and encourages you with warm nourishing words, how does that feel? When someone is kind and understanding, supportive and encouraging towards us, the hormone oxytocin is stimulated and we feel soothed and calmed.

We can also stimulate the soothing – contentment system by learning to be kind and supportive to ourselves. If we send ourselves helpful messages when things are hard for us we are more likely to stimulate those parts of the brain that respond to kindness. This will help us cope with stress and set-backs because we are rebalancing the emotional systems in our brain, and there is a growing body of research that shows that this is the case.

It’s worth noting that for many people who are self-critical, the idea of self-kindness can seem like a weakness or an indulgence. After all isn’t it the self-critic that keeps them on their game? Wouldn’t they simply make more mistakes, behave badly and lose motivation if it wasn’t for the self-critical voice? Isn’t it the ‘self-critic’ that keeps our lives from going down the pan!? The simple answer is NO!

It’s true that we need a moral compass, a sense of what’s right and wrong and the ability to constructively evaluate the results of our actions and to implement changes if needed – but this is very different to the derisive internal voice that extrapolates any mistakes that we might make into a slow and painful character assassination! It’s generally agreed that children respond best when there is support, love, encouragement and an acceptance of the inevitable process of making mistakes that being a human being involves. As adults, we’re no different. Self-kindness, rather than leading to selfishness and self-indulgence actually nourishes and motivates us to be at our best.

Consistency.

If we go for a walk on the mountain then the easiest path to follow is the one that’s already been well worn, but it might not take us to where we wish to go! If we want to go in a different direction then we might have to create a new path. We might have to walk through some ferns. It might feel a little uncomfortable and strange at first but we make it. The next time we take the walk then the new path becomes a little easier to follow. If we repeat the walk consistently then the new path becomes well worn and familiar, just like an old friend. The old path in turn becomes overgrown and less familiar to us.

Developing new habits is much like taking this walk on the mountain. Self-kindness is a skill and as with any skill, if practiced consistently, it can become a positive habit. Self-kindness meditation is the way in which we learn and practice this skill, so that when we go about our daily lives the habit of kindness follows us like a shadow or a friend.

In summary, the ABC of compassionate thinking consists of developing an Awareness of the pattern we’re currently running, Breaking the pattern with kindness, and doing this Consistently. Learning and practicing mindfulness allows us to develop this effective approach to overcoming our ‘inner critic’.

Our brains have been designed by evolution to need and respond positively to kindness. Practicing the habit of self-kindness through meditation is no more self-indulgent than training your body to be fit and healthy is self-indulgent. And, just as our body needs certain vitamins, minerals and a balanced diet to operate at its optimum then our brain also needs to be nourished. Self-kindness, therefore, is simply a question of treating our mind wisely and nourishing it with the food is so desperately needs.

Everyday Mindfulness

by Christopher Joseph

With so many words written about mindfulness these days it’s easy to become confused about what mindfulness is and how we can apply it to our everyday lives. How can we live a mindful life?

A definition of mindfulness which I very much like is one used by Bangor University’s centre for mindfulness research and practice:

“Mindfulness is cultivating the quality of being awake, present and accepting of this moment’s experience. This has a transforming potential on how we are with ourselves, how we are with others and how we are with stressful, difficult and challenging situations”.

The first part of this definition is about allowing ourselves to become aware and to connect with our present moment experience. The second part points to the transformational benefits such as calmness, centredness and confidence that we can feel from being in acceptance of our experience in this moment.

So, is this how we are in our everyday life – fully present, connected and accepting of our experience in each and every moment?

The honest answer for myself is no! Sometimes I’m able to live in this way for brief periods but there is definitely a gap to be bridged, a skill to be developed, and this is why I practice mindfulness.

But, how can we practice mindful awareness and acceptance in a simple, practical and everyday way?

The simplest answer to this question is based on one technique and two words: ‘In and Out’. I’m not talking about the hokey cokey! I’m of course talking about our breath. Yes, that’s right – the one that’s going in and out of you right now!

The breath is a wonderful thing. As well as being nourishing and life affirming at a physiological level it’s also a constant companion for us. It’s a ‘friend’ that we can connect with in any moment and use to anchor and ground ourselves in the present. If you’re unsure if this is the case then it’s worth reflecting on the fact that the calming effect that many people get when they smoke comes as much from the three minutes of deep connected breathing that they do than the chemicals inside the cigarette!

The breath also has two distinct phases to its cycle – an ‘in’ phase and an ‘out’ phase. We can use these two phases when practicing mindful awareness and acceptance. We can ‘breathe in’ an awareness of our experience on the in-breath and ‘breathe out’ a kindly acceptance of our experience on the out-breath.

Go on… try it now! As you breathe in right now take in an awareness of your experience, and then breathe out an acceptance and acknowledgement that this is your present moment experience right now.

When we begin this practice it’s good to start by focusing on our felt sensory experience and by concentrating on one element of it with each breath cycle. e.g. we could breathe in an awareness of the sense of the contact between our body and the chair, and then breathe out a deepening acknowledgement and a sense of sinking into this experience more fully.

We could play with doing this for a few breaths and then move onto another aspect of our experience – maybe the rise and fall of our stomach. Breathing in a fresh awareness of how this feels with every in-breath and then breathing out and dropping down into the richness of the experience with each out-breath. Again, play with this for a few breaths before moving on to focus on another aspect of your experience, maybe the sense of the air as it comes into the nostrils or the mouth and becomes the breath inside, before returning back out into the world on our out breath.

In this practice we use the in-breath to welcome in the experience with awareness and the out-breath to settle-into and touch our experience before finally letting it go. Through breathing in awareness and breathing out kindly acceptance in this way we are learning to become containers for our experience. Just as air can flow into a container and can be held by the container momentarily before flowing out again, so we to can also become containers for our experience – welcoming the experience, holding the experience and when appropriate letting the experience go before moving onto the next experience.

This of course becomes more challenging when our present moment experience is not as we would like it to be! As part of the rich tapestry of being a human being we experience strong thoughts, feelings and emotions that instinctively we don’t want to feel. Our open containers suddenly develop a narrow neck and we find it difficult to take in new experiences, and let go of old ones. This lack of flow and circulation of experience can result in stagnation which often manifests in unhelpful spiral thinking and sometimes catastophising.

So, how do we deal with this tendency to ‘block’ or ‘drown’ in our experience when it becomes difficult?

By recognising that the difficult thoughts, feelings and emotions that we experience in stressful and challenging situations are firstly, natural to have, and secondly, are not us – just as the air inside the container is not the container!

The ‘In/Out’ approach to everyday mindfulness as outlined above is still the same even when we have difficult and challenging experiences. The quality of the out breath, however, requires a far greater softness, warmth and kindness so that we can be open to accepting that in this moment this is how my experience currently is, whether I like it or not! It’s worth noting that since there is only one moment – this moment, we can only ever accept our experience in this moment. The Latin root of acceptance is Capere, which means to touch, to feel, to be with our experience in this moment. It doesn’t mean some downbeat resignation to things always being this way.

Through this practice of kindly acceptance we can open up the neck on our container of awareness so that we become more receptive to new experiences and are more able to let old ones go. This is a very liberating and transforming way of working with stressful, difficult and challenging thoughts, feelings and sensations.

To summarise… every breath we take we have the opportunity to breathe in awareness and to breathe out kindness and acceptance of this moment’s experience. This may be through breathing into tension in the body and breathing out – letting go of resistance to it. It may be through breathing in an awareness of challenging thoughts and strong emotions and breathing out a kindly acceptance of them and acknowledging that they too will pass. Or, it may be through breathing in an awareness of other peoples challenging behaviours and breathing out kindness and well wishing towards them!

We can also breathe in awareness of pleasant experiences and breathe out gratitude for having them…. the warmth of the sun, the kind words of a friend or a sudden release of tension in our body.

That’s it! – That’s as simple as everyday mindfulness gets! Breathing in awareness of our experience, breathing out kindness, acceptance and gratitude for that experience… and the beauty is that we have about 23,000 opportunities each and every day to practice it!.. Let me know how you get on?

Be the Difference Today

by Christopher Joseph

In February 2015 the ‘Be the Difference Today’ movement was launched by my friend and cousin Rich Waterman (www.bethedifference.today).

It has been established to support people in allowing them to celebrate who has been the difference for them in their lives and also to encourage recognition and acknowledgment of when they have been the difference for themselves and possibly others, even if only in some small and simple way. This is not some drive to bolster egos but an honest and genuine appreciation of times when we, or others, have been, or are being the difference. This recognition might be through the sharing of a personal story that ends up inspiring others, or it might be in the silent recognition of an important difference that we feel someone has made for us.

The ethos of this movement is very much in line with celebrating and ‘letting in the good’. This is a critical factor in appreciating and becoming contented with our life and ‘hardwiring our happiness’ as I wrote about in a recent article: ‘Hardwiring Happiness with Mindfulness’.

When I first learnt of this movement I felt a very strong connection with its name: ‘Be the Difference Today’ and I immediately felt it’s alignment with mindfulness. On reflecting as to why I felt this connection there are three key points that have arisen, and that I’ll address in this article:

1: It’s ‘Be the Difference Today’ not ‘Make a Difference Today’.

We currently live in a frantic world, in which we are subject to pulls and distractions on our attention at a level that we have never experienced before. As T.S. Eliot wrote we are often “Distracted from distraction by distraction!”

We also live in a world in which success and achieving has become intrinsically linked with what we do rather than who we are. This is dangerous, because a life of frantic ‘doing’ and operating constantly in the achieving mode in order to build our self-esteem creates fragile foundations! When our self-esteem is based on a judgement about how well we are doing in comparison with others, no matter how subtle, then low self-esteem is only around the corner whenever those comparisons become less favourable in our eyes! This can potentially be the start of a slippery slope that leads to feelings of low self-worth, anxiety and sometimes depression.

A result of living in the ‘doing mode’ rather than the ‘being mode’ is that we often spend far more time in our head (conceptual thinking) rather than our body (perceptual awareness). This can lead to us feeling disconnected with our body and also to the world around us, since we perceive this world through the 5 bodily senses of sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell.

‘Be’ the difference today puts the emphasis on the importance of ‘being’, of inhabiting our body and connecting with ourselves, others and the world around us in each and every moment.

A nice antidote to the striving definition of success given above is that used by Ben Zander who is the conductor of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and also a passionate motivational speaker. His definition of ‘success’ is based on whether the eyes of the people around him are shining? If they’re not shining then he gets to ask himself a powerful question: “Who am I being, or not being, that the eyes of the people around me are not shining?” This leads us on to the second point…

2: We are having an effect, or ‘being the difference’, in each and every moment whether we like it or not!

Unfortunately there is no opt-out here! As soon as we get up in the morning and enter the conscious state then we are having an effect on ourselves through the quality of the thoughts we give attention to, and on others through the quality of our speech and actions. We have a responsibility!

The word ‘responsibility’ often carries a heaviness with it in its everyday usage – I have a responsibility to my family, children, work, colleagues, parents etc. However, if we break the word down into its component parts then it simply means ‘the ability to respond’. This ability that we have to respond to a situation is not always immediately obvious when we’re in the throes of life. For many people this can be a massive realisation when they start practising mindfulness – they actually have the ability to choose to respond creatively, rather than react habitually, to their situation no matter how challenging that situation may be.

Our ability to respond creatively to what the world throws at us is definitely increased when we inhabit the ‘being’ mode and are more connected with ourselves and the world at large. When we get caught in the ‘doing’ mode we are more likely to be running on unconscious autopilot and as a result we can often react habitually to events without even realising it until later!

Living more from a place of being doesn’t mean, however, that we don’t do anything! When we are fully able to be with ourselves and accepting of ourselves then a great energy can often be released as we drop the story of ‘me’ and ‘I’, even if only for a brief moment.

This state of being and its associated energy release is often called the state of ‘flow’, and it can be a very pleasurable, creative and often active state to be in. This is far from the sedentary mode that often gets associated with ‘just being’. In fact, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in his book ‘Flow’ talks of all kinds of people including composers, artists and also sportspeople who can enter this place of being and the very creative action that can often arise as a result.

The ‘difference’ that we become for ourselves and others can therefore simply be attributed to how we ‘are’ – our level of ‘being’ or ‘presence’ in the moment, but also to the actions that spring from this place of being, from this deeper, wiser, more mindful and connected place. These actions, because they flow from us rather than being forced out of us, are more spontaneous, freer and congruent with who we are as human beings.

The other important word in the phrase is of course the word ‘today’. Just like everyone else I have at times in the past put things off and delayed in taking action on something I knew was the right thing to do… and usually regretted it afterwards! The ‘today’ part of ‘be the difference today’ reminds me of the ‘now-ness’ of this precious opportunity to live more from a place of ‘being’.

But why do we need this reminder? After all we are called ‘human beings’ not ‘human doings’! This brings us onto the third and final key point:

3: This is a practice!

Whilst it is true that as ‘human beings’ the state of ‘being’ is our most natural state, it is unfortunately not our most common state. It has been conditioned out of us by the constant and ever increasing calls and demands of this ‘doing-based’ world. As soon as you finish reading this article, or possibly whilst still reading it, you’ll probably be distracted by something – maybe the ping of an SMS alert, email pop-up, phone call, front door bell or your boss!

It’s difficult to remain seated in a place of being connected with the body when there’s so much trying to pull us into the conceptual, thinking, head-driven mind. This is why we need to practice ‘being’, and one clear way of doing this is through the practice of mindfulness.

Practices such as the body scan, mindfulness of breathing and mindful movements can help us connect with our body. Mindfulness of sounds, our surroundings and daily activities help us to connect with the world, and through kindness meditations we can connect more deeply with ourselves and others.

These three points summarise why I feel such a strong connection with the phrase ‘Be the Difference Today’. It’s a reminder to me for the need to move from the busyness of ‘doing’ to the stillness of ‘being’. It’s a reminder to me that I have a ‘response-ability’ – I’m having an effect simply by my presence in this world so I may as well do what I can to make this a positive difference, and to do this today. It’s also a reminder that in order to increase my chances of ‘being the difference today’ for myself and others in a positive way, no matter how small, then I need to practice. For me that practice is mindfulness, because for the last 7 years it’s allowed me to live far more from a place of awareness, kindness and contentment than anything else I have ever done in my life.

‘Be The Difference Today’ is therefore, in my eyes, a strong and powerful call to practice… to be present.

What does it mean for you?

The Paradox of Mindfulness

by Christopher Joseph

With the beginning of a New Year comes the traditional tendency to reflect on the past year and make resolutions or set goals for the coming year. But what place, if any, does mindfulness have in this?

With the beginning of a New Year comes the traditional tendency to reflect on the past year and make resolutions or set goals for the coming year. But what place, if any, does mindfulness have in this?

Mindfulness is almost always portrayed as being synonymous with present moment awareness – of being ‘in the moment’. Being aware of our present moment experience such as bodily sensations, thoughts and feelings is a large part of mindfulness but it’s not the full story.

If we follow the origins of mindfulness to its Buddhist roots then we find two dimensions of awareness that are referred to: ‘Sati’ which is the Pali word for ‘bare awareness’, and; ‘Sampajanna’ which is often translated as ‘continuity of purpose’.

This ‘continuity of purpose’ is like the thread that runs through our lives. Whilst a stream may be ‘captured’ in a moment by a photograph it is far more than the photograph – it has a source, a present moment flow and a direction. As do our lives. Unlike a stream, however, whose direction of flow is largely governed by gravity, the lie of the land and water that has gone before it, we have far more choice over the direction of our lives, even if at times we can’t ‘see’ this choice. (For further exploration of choice in the context of mindfulness see my article “5 Steps to Mindfulness”).

Sometimes, people who meditate are viewed as ‘lofty’ people who don’t have a thought for the past nor a care for the future – they just go with the flow! In my experience this is generally not the case! This view does however begin to illustrate the paradox of mindfulness. In the conventional sense, success is based on the achievement of goals i.e. getting from ‘A’ to ‘B’ in a particular endeavour – be that education, sport, music, weight loss or even mindfulness itself. By definition ‘A’ is portrayed as some inferior state to the desirable state which is ‘B’. Since ‘B’ has not yet been achieved this sets up a tension which can be motivating, but it can also be destructive and stressful if we, in our striving, are constantly rejecting ‘A’ – because ‘A’ is our present moment experience – it’s who we currently are!

This is the paradox of mindfulness, which lies at the heart of mindfulness practice: if you want to get from A to B, you have to really be at A!

If for example you’re overweight and become short of breath when climbing the stairs and you wish to lose weight and gain fitness. Rather than making effort to stop and block-out the associated unpleasant and anxious feelings (which tends to make us feel more anxious), we can ‘turn towards’ the anxiety and explore it with a kind curiosity. Where do you feel it in your body? How does it actually feel? In doing so we can stay in tune with our body, which is essential if we are going to be able to pick up on the important feedback from our body in relation to the effect of the food and movement we give it. More importantly we can’t enjoy the process of losing weight and becoming healthier and fitter if we are numb to our bodies!

Be careful though – ‘A’ in this case is not the secondary experience of all the thoughts, additional feelings, judgements, analyzing and problem-solving that usually accompany our feelings of anxiety about being overweight and unfit for example. ‘A’ is the primary experience – our direct, felt, moment by moment bodily sensory experience of the anxiety we’re currently feeling in relation to our health.

Mindfulness is, therefore, about being fully at ‘A’, about accepting and being with our present moment experience, warts and all. But for mindfulness practitioners this doesn’t mean that there isn’t a ‘B’, or, if not a ‘B’, then at least a direction that we wish to go in – a ‘continuity of purpose’.

This continuity of purpose or direction might be different for different people. For me personally, there is a more mindful me that I wish to step into, a more compassionate me, a wiser me, a calmer, stiller, more centred me. Whilst I don’t set New Year’s resolutions myself in the conventional sense I do hold aspirations. My practice is therefore a balance which is centred around recognizing the value and importance of these aspirations, which give me a direction of where I’d like to go to and a continuity of purpose, but also at the same time fully acknowledging my present moment experience of where I’m currently at.

When Ellen MacArthur broke the world record for the fastest solo circumnavigation of the globe on the 7th February 2005 she’d had to evaluate and reevaluate her position, the environmental conditions and her own physical and mental condition countless times to make the necessary adjustments to stay on course. In the same way we also have to honestly evaluate our own environmental and personal conditions if we are to maintain our own course, our own continuity of purpose. The real beauty of a sustained mindfulness practice in its wider context is that rather than the once yearly New Year’s evaluations and resolutions we are able to maintain a far more regular, detailed and objective view of our ourselves so that we can maintain course and follow our own path.

Hardwiring Happiness with Mindfulness

by Christopher Joseph

Happiness is a state of being that is accessible in any moment, and is not directly dependent on our external conditions. There are countless examples of people having experienced often profound states of happiness despite very challenging personal circumstances, and you too might well have had feelings of stillness, contentment and possibly happiness, even when things around you have not always been as you would like them to have been.

Happiness is a state of being that is accessible in any moment, and is not directly dependent on our external conditions. There are countless examples of people having experienced often profound states of happiness despite very challenging personal circumstances, and you too might well have had feelings of stillness, contentment and possibly happiness, even when things around you have not always been as you would like them to have been.

Why, therefore is this state of sustained happiness, that we humans so often crave, so often elusive?

One of the main reasons for this is the very strong conditioning that we are exposed to by a society that emphasises and rewards achievement. As such we unconsciously learn to link happiness to achievement. I call this ‘rule based happiness’, and it’s something that I’m certainly no stranger to myself!

Rule based happiness essentially means that I will allow myself to take in the positives and feel happy once I have achieved ‘X’. It’s a pretty crude and essentially unkind way to motivate oneself, but it seems to be a very common pattern that humans run. I used this extensively, all be it unconsciously at the time, throughout my school days and particularly in my undergraduate degree in order to motivate myself – e.g. “If I can get ‘X’ % in this assignment then I’ll be happy!”.

The problem with this effective bartering system is that our happiness, and often our sense of self worth, becomes intrinsically connected with what we achieve rather than who we are. Our sense of happiness can then feel very fragile since it is strongly linked to our actions, and more specifically, getting particular results from those actions, which we are often not even in control of! Even if we do manage to create the desired outcome and achieve ‘X’, the sense of happiness is often fleeting since the ‘X’ is replaced by a ‘Y’ and then a ‘Z’ and so on, before we can give ourselves permission to feel ‘really happy’! The quality of ‘happiness’ that we feel in this context can also feel more like a momentarily relief of pressure rather than any sense of true happiness, since it is conditional rather than unconditional.

The net effect of running such a pattern, even at a subtle unconscious level, is that we simply become under practiced at being open to and experiencing in an unconditional way, states such as contentment, satisfaction, fulfillment and happiness. They therefore do not become familiar mental states for us. This can also result in us becoming stressed, since by constantly making our happiness dependent on something that we’re often not even in control of, we are denying ourselves the opportunity to access these soothing emotional states which stimulate the calming effects of our parasympathetic nervous system.

So, how can we address this issue of ‘rule based’ or ‘conditional’ happiness in a mindful way?

Since conditional happiness is based on allowing ourselves to feel happy when we achieve… or have… then it’s founded on a degree of non-acceptance of ‘what is’ in the present moment, even if we’re unaware of this. The underlying message that we’re sending ourselves is that the present moment is not good enough in some way.

The primary mindfulness practice, therefore, that serves as an antidote to this habit of ‘conditional happiness’ is the practice of acceptance – being prepared to be fully with our felt sensory experience in the present moment irrespective of whether that’s pleasant or unpleasant! I’ve described this practice previously in my article “5 Steps to Mindfulness”. Step 2, which is ‘Being with Unpleasant or Difficult Experiences’, involves a willingness to surrender to and accept ‘what is’ in the present moment. This is very different to, and NOT to be confused with, a resigned acceptance that it will always be like this in the future, because it may well not!

When we ‘drop the fight’ with our present moment experience by accepting rather than denying it then not only do we begin to feel more at ease and at peace with our current situation but the energy that was previously engaged with fighting our experience gets released. What we do with that released energy is important and this brings us on to the second way in which we can use mindfulness in respect to our happiness – we can use it to hardwire our happiness!

But, why do we need to do this?

When we’re washing our hair in the shower in the morning, are we engrossed in the pleasant sensual present moment experience of the activity, or are we thinking about all of the tasks and conversations that we need to have that day? Chances are that unless we’re already practicing mindfulness then it’s the latter. In addition, when we think about the tasks and conversations often it’s not in a positive light – “I’m looking forward to having the opportunity to practice my writing skills whilst working on that report and then connecting with my boss in my appraisal” is probably not the slant that our thinking is taking! If we then have the appraisal and our boss gives us 5 positive comments, 4 neutral ones and 1 negative one, which one do we dwell on in bed that night?!

This tendency to dwell on the negatives, to view things as potential threats and to look for what’s missing rather than what’s there is something that neuropsychologists believe is a deep seated human trait founded in our prehistoric past, and they call it the ‘Negativity Bias’. Dr Rick Hanson who has conducted research in this area says that “the brain is very good at learning from bad experiences but very bad at learning from good ones. Our brain is like Velcro for bad experiences but Teflon for good ones!”.

In order to get positive experiences to stick in our brain we therefore have to actively work at overcoming our negativity bias. This is very important since it is known that neurons that fire together, wire together. This means that with time, passing mental states become lasting neural traits. If left to its own devices without any conscious ‘training’ from ourselves these neural traits are likely to be biased towards negativity. This can cause feelings of stress which release cortisol into the body. This cortisol then travels to the brain where it causes alarm bells to ring in the amygdala, which is responsible for memory, decision-making and emotional reactions. The cortisol also gradually kills off neurons in the hippocampus, which as well as playing a major role in short to long term memory consolidation and spatial awareness, also serves to ‘calm down’ the amygdala and feelings of stress as a whole.

The positive findings from the research, however, are that all the experiences we want e.g. feeling calm, loved and happy are not just constructed from the brain but can be built into the brain. The mind can change the brain to change the mind, as Dr Hanson puts it.

Most of our inner strengths are built from positive experiences of having those inner strengths. If you want to have a more loving heart, for example, then you can practice more moments of kindness and compassion towards yourself and others. If you want to be more calm and confident then you practice entering those states of calmness and confidence more often.

We can therefore hardwire our happiness with mindfulness by seeking out the pleasant and letting in the good. Rick Hanson describes this simple yet potentially powerful practice in his TEDx talk carrying the same title as his book – ‘Hardwiring Happiness’.

You can practice this by bringing to mind someone you know who cares about you – maybe a friend, family member or even a pet. Feel the experience of being cared for, and really absorb it, letting it sink into you as you sink into it. Continue to let this warm, pleasurable and comforting experience of being cared for suffuse your being for 20-30 seconds, so that it can be transferred from the short term memory buffers to the long term storage.

The practice in its essential form can be summarised as follows:

- Have (or seek out) a positive experience.

- Enrich the experience.

- Absorb the experience.

In itself this single practice won’t change you overnight but it does cause good neurons to begin to fire together, and with time and practice they will begin to wire together, thus physically changing the way our brain is built and as such the outlook of our mind.

It should be noted also that the practice is not about denying negative or unpleasant truths. Paradoxically the more we are able to take in the positives then the better placed we are to be able to turn fully towards the negative aspects and see them for what they are and not more than they are.

This practice is not about naive Pollyanna thinking either, but about reclaiming control of our brains stone age bias to overly focus on and worry about ‘perceived threats’. The most important moment we have, in fact, the only moment we have is this one. What will we do with it? Will we waste it in worry about something that might never happen in the future? Or, will we use it to consciously take in the good, and rest in the spacious awareness of simply ‘being’ that is open to each and every one of us in each and every moment?

Life can change dramatically when we stop confining ourselves to only letting in feelings of happiness once we have taken a particular action, achieved a certain result or attained a specific thing. Instead, when we choose to first feel happy and then let our actions and behaviour flow from that positive mental state, then life goes from feeling confined to becoming a world of possibility.

Mindfulness for Weight Loss

by Christopher Joseph

Obesity rates over the last 25 years have quadrupled, and a survey published in 2012 found that just over a quarter of all adults (26%) in England are obese. A further 41% of men and 33% of women are classed as overweight. In Wales, a recent report has found that 1 in 4 children are obese by the age of 11, and there are estimates that by 2050 over half of the UK population will be obese. Type 2 diabetes, which is just one of the associated problems with obesity, already costs the NHS an estimated £9 billion a year, which is about 10% of the NHS budget.

Obesity rates over the last 25 years have quadrupled, and a survey published in 2012 found that just over a quarter of all adults (26%) in England are obese. A further 41% of men and 33% of women are classed as overweight. In Wales, a recent report has found that 1 in 4 children are obese by the age of 11, and there are estimates that by 2050 over half of the UK population will be obese. Type 2 diabetes, which is just one of the associated problems with obesity, already costs the NHS an estimated £9 billion a year, which is about 10% of the NHS budget.

The current approach to weight loss is primarily diet-based, and all diets are fundamentally based on the principal of restricted food intake in line with some formulated plan. Diets are very seductive for two reasons. Firstly, they provide guidance on what to eat and often when to eat it. As such they take the onus and responsibility off us from actually listening and responding to what our body needs when it needs it. Secondly, diets have the illusion of working – at least in the short term. However, since by their very nature they require control, will power and over-riding the natural signals that our body’s sending us they are unsustainable in the long term. Not only do diets not work in the long term, many people become entrained in the diet trap, which is detrimental to the health of our body and the health of our mind in respect to the way we view our body.

The diet trap is described thoroughly by Jason Vale in his book “Slim for Life: Freedom from the diet trap”. In essence it’s instigated when we decide to go on the latest diet for whatever reason, be it an unhappiness with the way we look, the way we feel, or pressure from someone else. We force ourselves using ‘will power’ to follow the prescribed plan, we stop listening to our body signals (that are shouting hunger), become irritable, miserable and uncomfortable around food.

Due to the often severe reduction in food intake our body goes into survival mode and as a result our metabolic rate (rate at which we burn food) drops! After a period of time we are unable to continue to override the messages from our body, which we label as our ‘will power’ running out! We then ‘drop’ the diet and overeat to compensate for the ‘diet stress’ we have put ourselves through. Since our body is still in ‘starvation mode’ it’s unsure when and where the next meal is coming from so it grabs everything it can! – i.e. it stores fat far more readily in preparation for the lean times it thinks are soon coming again.

As a result of this process, over time, we end up heavier than when we started the diet!… so, what do we do?… yes, that’s right!… we go on another diet and go back to the start!… and, so the physically and emotionally painful compounding effect of the ‘yo-yo’ diet cycle continues.

So, what is the alternative? What is the mindful approach?

The mindful alternative to the diet trap is to learn to trust yourself again to eat what you need, when you need it.

But how do we do this when we have been spending years turning away and trying to disconnect from our body either because we dislike the way it looks and feels, or because it’s screaming hunger at us when we’re starving ourselves on the latest diet?

The answer is through establishing a mindfulness practice which is focused on connection (or reconnection):

- Connecting with food and the enjoyment of eating it.

- Connecting with our body and the enjoyment of moving it.

- Connecting with ourselves and others and the enjoyment of feeling that we have a part to play in this world.

These three vitally important areas of connection can be achieved through mindful eating, body scan meditations, mindful movement and kindness practices towards ourselves and others.

The net result of practicing these three areas of connection is that we become far more in tune with our food, our body, ourselves and our lives. As such we are far better placed to make better choices around what we eat, how much we eat and when we eat it. Losing weight, feeling healthier and becoming more energised are simply ‘side-effects’ of this connection process! – Very positive side-effects nonetheless!

As you’ve hopefully realised by now, this process of mindful connection, or reconnection, is a practice. We are talking about replacing potentially years of habitual tendencies to disconnect, either consciously or unconsciously, with our eating, our body, ourselves and sometimes other people and even the world. As such this requires an element of education, of training and of course practice.

5 Steps to Mindfulness

by Christopher Joseph

In 1976 Vidyamala Burch suffered a severe spinal injury when she was just 16 years old. In 2001, after many years of exploring mindfulness and meditation as a way to manage her condition, she founded Breathworks. Breathworks is now an internationally recognised and highly respected organisation that delivers mindfulness training in the areas of pain management and stress reduction. One of the cornerstones of the Breathworks approach to mindfulness has been the ‘5 Step Process’. In this article I’ll explore these ‘5 Steps’ and give examples of how we can practice them in our daily lives.

In 1976 Vidyamala Burch suffered a severe spinal injury when she was just 16 years old. In 2001, after many years of exploring mindfulness and meditation as a way to manage her condition, she founded Breathworks. Breathworks is now an internationally recognised and highly respected organisation that delivers mindfulness training in the areas of pain management and stress reduction. One of the cornerstones of the Breathworks approach to mindfulness has been the ‘5 Step Process’. In this article I’ll explore these ‘5 Steps’ and give examples of how we can practice them in our daily lives.

The ‘5 Steps’ are simply a framework for mindfulness which we can use to better understand our experience and get to know ourselves a little better. Whilst there is a general element of progression through the stages we will also find ourselves revisiting stages time and time again as our practice develops.

Step 1: Awareness

Developing a ‘bare awareness’ of our present moment felt experience is an essential starting point for the cultivation of mindfulness. Without awareness we are blind to how we are in the moment, we are on autopilot, and we inevitably react to life events in old habitual ways.

When I first began practicing mindfulness the development of bare awareness was a revelation to me. Being able to tune in to my moment by moment felt experiences within my body, to watch thoughts and feeling arise and then dissipate, and to observe situations when my buttons were pressed without reacting in old habitual ‘knee-jerk’ ways felt very liberating, even if at first I was only able to catch glimpses of this state of being. Without realising it, for many years I had been a slave to my insecure thinking, but now through awareness, a space had begun to open up between my thoughts and my response to them. I was finally able to see that thoughts were not necessarily facts!

Awareness can be practiced in very simple and straight forward ways. In this very moment we can bring attention first of all to the points of contact between our body and the chair or the earth beneath us. We can then tune in to our breath and the movement of our body with our breath – maybe the expansion of our rib cage and the rise and fall of our stomach. We can then turn our awareness to our posture and the position of our spine, developing an overall sense for how it feels to sit here right now. We can then broaden our awareness to take in sounds around us whilst staying with the felt sense of our breath.

This process of developing awareness of the felt sensations in our body, moment by moment, is not complicated but it’s extremely challenging! The mind has other ideas about what we should be focusing on. Thoughts will inevitably come up and will constantly try and pull us out of our sensory experience of our body and into the world of problem solving, judging and evaluation. The process of coming back time and time again from this ‘doing mode’ into more of a ‘being mode’, and all of the insight that this brings, is the process of developing awareness. One of the benefits of this in respect to thoughts is the shift in perspective that this provides – we are more able to look at our thoughts rather than from our thoughts.

Step 2: Being With Unpleasant or Difficult Experiences

When we begin to develop more awareness we also become more aware of the habitual ways in which we have previously dealt with the unpleasant aspects of our lives. For example, we might notice a tendency to block our experience by turning for that extra drink or eating excessively due to difficulties at work or within a relationship. Alternatively, we might notice a tendency to drown in our experience by catastrophising, overanalysing or excessively talking at length about our problems with others.

The second step can of course be very challenging depending on the nature of the difficult experiences you’re working with. Deep down however we usually know that it’s work that needs doing since the alternative of trying to ignore or shut out our experience rarely works in the long run, and often makes the situation worse. In addition, when we shut off from the difficult aspects of our experience we also, almost by default, shut off from the pleasant aspects of our experience as well – our band of awareness can become very narrow and we can end up feeling isolated and a little numb to the world.

This second stage in about acceptance. Not acceptance in terms of putting up with, or resigning ourselves to a particular situation, but acceptance of our present moment experience, however that may be. Acceptance comes from the Latin capere, which means to touch. Acceptance can therefore be thought of as our willingness to have the experience, to touch it, to feel it, to be with it. As such it’s quite an active and positive activity although it can feel challenging if it’s not what we’re currently used to doing!

In this step, maintaining a positive, kind and light receptivity to our experience is absolutely essential. In my experience maintaining a sense of humour also helps immensely! One practical way in which we can practice this step is by gently bringing an unpleasant or difficult aspect of our lives into our consciousness and then practice being with the experience. We can watch our experience unfold in the felt physical response of our body. This is best done after some experience of meditation, when you’re in a relatively positive state of mind, and initially with something that you find only mildly difficult.

Step 3: Seeking Out the Pleasant

In conjunction to being with the unpleasant aspects of our experience we also need to seek out the pleasant – It isn’t all doom and gloom!

Recent research in neuro-psychology has shown that we, as a human race, do have a ‘negativity bias’. In our primeval days we needed to be alert to dangers to ensure survival. Real dangers to our lives are now rare but our brains still perform this function i.e. we look for potential threats, find faults and see the negative more readily than the positive. Research has also shown that negative experiences get almost immediately stored in the memory whereas positive experiences need to be held in awareness for a dozen or more seconds to transfer from short-term memory buffers to long-term storage. The neuro-psychologist Dr Rick Hanson says that the brain is “like Velcro for negative experiences but Teflon for positive ones!”.

‘Seeking’ is therefore an apt word in the title of this third step to mindfulness. It suggests the need to actively focus on the pleasant aspects of our experience in order to maintain a balanced awareness of our overall experience. The pleasant aspects of our experience are just as valid as the unpleasant aspects, although we may have to undo a lot of conditioning before we can fully realize this.

On a practical level we may notice a warmth, a release of tension or a sense of aliveness in the body during meditation as we practice this step. In our daily lives we might notice the flight of a bird, the smell of a flower or the sound of the wind in the trees.

Step 4: Becoming a Bigger Container

By learning to be with the unpleasant and to seek out the pleasant aspects of our experience we are continually broadening our present moment awareness – we are in effect ‘becoming bigger containers’.

This stage is about developing equanimity. Equanimity is the ability to hold pleasant and unpleasant experiences within our awareness with equal regard. We avoid the tendency to try and push away the unpleasant and to cling to the pleasant, but instead let ourselves be with the diverse aspects of each moment as they come into being and pass away, moment by moment.

If you imagine your mind as a container and the water inside as your awareness, then it becomes apparent that if a drop of red dye representing an unpleasant experience is dropped into the water and a drop of blue dye representing a pleasant experience is dropped in then our overall awareness is going to be far less ‘coloured’ by the dyes if our containers are large and full of water!

Through learning mindfulness and practicing it regularly we can become far bigger containers, and as such more balanced, equanimous and emotionally robust.

Step 5: Choice

If we follow the origins of mindfulness to its Buddhist roots then we find two dimensions of awareness that are referred to: ‘Sati’ which is the Pali word for ‘bare awareness, and; ‘Sampajanna’ which is often translated as ‘continuity of purpose’.

Mindfulness of the present moment through bare awareness of our experience is often talked about, but a lesser explored although equally important aspect of mindfulness is mindfulness of our path. The choices we make in each and every moment determine the direction we take in life. If we wish to stay on course then we need to maintain clear vision so that we can make the appropriate choices at the appropriate times. It is through developing awareness and becoming a ‘bigger container’ that we are more likely to be able to hold all of our experience and maintain clear vision so that we can make the right choices for us.

Choice is implicit is each of the first four steps given above, but it’s also a key step in itself. Practicing mindfulness can be extremely liberating since we can start to see that we have choices where previously we might have felt that we had none.

Choice is also a muscle that needs flexing. When we become stuck in routines then this muscle can begin to atrophy and weaken. We can strengthen this muscle by exercising our choice, firstly in small ways then moving on to bigger decisions. On a practical level this might be as simple as changing your route to work, taking a different filling in your sandwich or reading a book rather than watching the T.V. Then you can move onto the bigger decisions like signing up for a mindfulness course!

In its simplest form mindfulness can be thought of as the process of knowing yourself. It can be a very humbling process at times, since it can shine a light on habits that we were previously unaware of. Through practice, however, and following the five steps listed above both in meditation and in our daily lives, we can get to know ourselves at a level that we never thought possible. This is possibly the most precious gift of all, since with insight into our character and a deeper insight into our true nature and purpose comes the possibility of change. As the author Vajragupta puts it: “Mindfulness is the first crucial step to our inner freedom, to becoming more fully the ‘author’ of our own story”.

The Mindful Chimp

by Christopher Joseph

We all have times when someone or something pushes our buttons and we react. In his book “The Chimp Paradox” Professor Steve Peters labels this reactionary emotional part of our brain as the ‘inner Chimp’! Whilst we may not choose the same label as Professor Peters to describe this aspect of our own mind we can probably relate to it within ourselves… I certainly can!

Peters in his book takes quite complex information about the physical structure of our brain and creates a simplified intuitive psychological model that explains how each component contributes to the inner experience of our minds on a daily basis. The three main components of his model for the mind are the ‘inner Chimp’, the ‘Human’ and the ‘Computer’.

The inner Chimp is the emotional part of our brain, designed by evolution from a prehistoric past to support our survival. Its thinking is based on interpretations and impressions rather than facts about a situation. It’s rooted in feelings of fear, paranoia and the need for survival.

The Human mind considers the evidence and uses cognition to reach careful and deliberate conclusions. It’s said to be where our highest values as humans reside, and it can be considered to be ‘us’ i.e. the you or me that we wish to be in this world. The Human and the Chimp have independent personalities with different agendas, ways of thinking, and modes of operating.

The third component, termed the Computer, is our bank of memorised automatic habits, responses and experiences. Some of these we will view as ‘bad’ and some ‘good’, and this is where both our Chimp and our Human facets look for similar experiences that they will associate with when processing what’s currently happening to us.

In his simplified model Stevens equates the Human, the Chimp and the Computer to the three psychological brains, namely the frontal, limbic and parietal. Usually these three brain regions work together, but sometimes one of them can take over complete control! If the Chimp within us takes over then we can become emotionally reactionary. Depending on the context of the situation this is not necessarily a bad thing. The Chimp can be your best friend but it can also be your worst enemy, even at the same time! Therein lies the paradox.

A key point in explaining why our emotional inner Chimp can react so quickly is that the limbic system with which it is associated works about five times quicker than the Human frontal lobe.

So, what’s all this got to do with mindfulness?

Quite a lot I believe! I think that Stevens’ model, all be it very simplified, can be a useful framework for working with the mind during mediation as well as daily life.

Mindfulness can offer us a very powerful and effective means of: understanding; befriending, and managing our Chimp, so that our true Human side can become ever more prominent and flourish.

The first stage of mindfulness is developing present moment awareness of what’s going on for us right now. With practice, over time our awareness will expand to include insights and an understanding of the emotional, potentially reactionary side of our minds – our ‘inner Chimp’. We will come to learn when, how and why it reacts the way it does, and through greater understanding of our Chimp we will be far better placed to make wiser decisions and choices in the future.

Another key element of mindfulness is maintaining a kind, light-hearted and non-judgmental attitude towards ourselves, and this of course includes our Chimp. We need to befriend our Chimp. Stevens’ models is very useful in this respect as he makes the clear distinction between us the Human, and our primeval reactionary Chimp. This ancient part of our brain was designed through natural selection to keep us safe in a very dangerous prehistoric past. However, it’s fast, strong and often vicious responses don’t often help resolve many of the complex 21st century challenges we are now faced with. The Chimp is always active when we are unsettled or worried, it tends to think in black and white absolute terms, can be prone to paranoia, and often catastrophises things.

At times when our emotions dictate our behaviour, and we react to a situation, the emotional machine that is our Chimp is in effect overpowering our Human mind. I think at times like these when we may speak or act in ways we later regret, it’s useful to remember that we are not our Chimp – we are not a ‘bad’ person beyond help! We’ve simply been momentarily hijacked by our five times stronger Chimp.

Recognising that our unhelpful reactionary behaviour is the result of our Chimp and not us (the Human) can be a very useful distinction in preventing over identification with our unruly Chimp which can lead to us mentally ‘beating ourselves up’, causing self-loathing, low self-esteem and over time depression.

This doesn’t absolve us of responsibility, however, and we can’t simply go around blaming our bad behavior on our Chimp! Having a Chimp is like owning a dog. You are not responsible for the nature of the dog but you are responsible for managing its behavior. Likewise with our minds – we’re not responsible for the fundamental nature of our mind but we are responsible for managing and training it.

Whilst the primeval reactionary aspect of the mind might not be something we have any say over when we’re born, we certainly do have a responsibility to understand, befriend and manage it so that it doesn’t hurt us or the people around us. Since the Chimp aspect of our mind is driven and feeds off our insecurities, then practicing meditations based on kindly acceptance of ourselves and kindness towards others is a vital component in befriending and quietening down our Chimp, so that we can respond more fully as a Human.

The Chimp brain is five times faster than the Human brain but the Computer brain is four times faster than the Chimp and twenty times faster than the Human. Because of this important fact we can use the Computer part of our brain, our automated habits, to initiate responses faster than the Chimp can react. Establishing new habits, by their very nature takes time and practice. This is where the true benefits of establishing a regular mindfulness practice really bear fruit. Mindfulness meditation is effectively a process of retraining our mind, in a good way.

In the body scan meditation for example we are training our mind to come back from distractive thoughts and to rest in an awareness of the present moment felt sensations in our body. In the mindfulness of breathing meditation we are similarly training our minds to come back time and time again to the physical sensations of our breath in the present moment. With kindness meditation practices, whether it’s kindness towards ourselves, a friend or others we are also practicing a new more flexible way of looking at our own experience and our attitude towards others.

On a practical level for example, when someone is unkind to us such as cutting us up in traffic, instead of letting the Chimp react with energetic hand gestures, flashing lights and a loud horn, you can remind yourself that they might be having a very difficult day, have an emergency to get to or simply didn’t see you and made a genuine mistake. In doing so you are far more likely to arrive safely at your own destination and in a good mood than if you let your Chimp do the driving!

Through regularly practicing mindfulness both during meditation and our everyday lives, we are choosing a new way of being: we are creating new grooves, laying down new neural pathways in the brain and establishing new positive habits.

So, next time you sense your ‘Chimp’ beginning to play up, remember to smile, be kind and to meditate!

3 ½ Helpful Hints for Becoming More Mindful of our Surroundings

By Christopher Joseph

Meditation is sometimes portrayed as a purely inward occupation – a naval gazing pursuit of knowledge about the inner landscapes of our mind! Whilst an awareness of our minds inner workings: our character traits; our predominant habits; our tendencies to judge etc. are useful insights that can be gained with practice over time, they are not the whole story.

Meditation is sometimes portrayed as a purely inward occupation – a naval gazing pursuit of knowledge about the inner landscapes of our mind! Whilst an awareness of our minds inner workings: our character traits; our predominant habits; our tendencies to judge etc. are useful insights that can be gained with practice over time, they are not the whole story.

Mindfulness is far more than just a ‘bare awareness’ of our internal makeup as individual human beings – it’s a rich and intelligent appreciation of our ever changing ‘internal environment’ of thoughts, feelings and emotions, in the context of the ‘external environment’ we currently inhabit.

It is often said that life is a dance, and this is true of the relationship between the ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ aspects of our mind. Many a time I have questioned why I feel a little tired, drained and lacking in inspiration, only to realise that I’ve been locked up in a dark office for several hours without having taken a break! (I say ‘locked up’ in a metaphorical sense of course before you start getting worried!)

Stress can often arise from a determined, sometimes slightly obsessive desire to control a particular aspect of our lives. We can often become fixated on getting a particular result, and when it doesn’t turn-out as expected we can sometimes become frustrated, annoyed and despondent. Often we re-double our efforts, and become increasingly more determined to control that which may not be completely within our control – we can become ever more narrowly focused on ‘solving’ a particular issue and lose sight of the ‘woods for the trees’.

This is exactly why developing the ability to be regularly mindful of our surroundings is so very important. It gives us the ability to ‘zoom out’, to see the ‘bigger picture’, to put things in perspective. In doing so we are able to develop a breadth and depth to our awareness, to feel more spacious – we can still see the trees but we also know that there are woods, and where we are within them!

So, how can we become more mindful of our surroundings?

Helpful Hint 1: Tune-in your senses.

One of my lasting memories of my grandmother’s house was the old TV set she had in the corner which came complete with an actual tuning knob for tuning in each of the four channels!

A key element of developing and staying mindful of our surroundings is learning to tune-in our senses. It might help to imagine that you have a tuning knob for each of your five senses. As you sit here right now reading this you can alternate individually through each of your five senses – your sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell and imagine that you are tuning each one in to their optimum level by turning the individual tuning knobs. If you actually do this simple exercise (and I recommend that you do try it) you will probably find that you develop an overall experience of your surroundings that is far richer than you’d had previously, and ultimately an experience that is far more interesting and engaging, and easier to stay mindful of.

Helpful Hint 2: Drop labels and judgements.

Easier said than done I know – but it’s the intention that’s key here.

So often we simply just do not take-in what’s around us. Our minds have a limited capacity for what they can process at any one time – we have a limited bandwidth so to speak. That’s exactly why we learn from an early age to compartmentalise things, to develop labels and judgements: That’s a chair; that’s a car; dark grey clouds mean the threat of rain and are bad, sun and clear blue sky mean fine weather and are good etc.

These labels and judgements are necessary in order for us to process everything that comes at us, and for us to function, but they can close us off from truly experiencing our surroundings if we never step beyond them. A key element in developing mindfulness of our surroundings in this respect is learning (or relearning) to experience the world afresh through the eyes of a child – learning to experience things again as if for the very first time.

Being in nature, because of its inherent primeval beauty and diversity, can play an important role in reigniting this child-like wonder about the world around us, as I have discussed in a previous article: “Nature and its Role in Mindfulness”. When we learn to begin to drop labels, concepts and judgements about our ‘natural’ surroundings then we are more likely to be able to foster the same attitude of curiosity to our more familiar ‘man-made’ surroundings such as home and work.

A useful mindfulness exercise to practice in this respect is to become particularly aware of one of your senses, such as listening to sounds. As you close your eyes and simply ‘take-in’ the sounds around you notice how readily your mind wants to label and judge each sound: E.g. traffic – unpleasant, bird song – pleasant. As you do this exercise see if you can step beyond this natural tendency to label and judge the sounds and simply ‘record/observe’ them as some form of ‘natural orchestra’. In doing so rest your attention on the quality (volume, tone, pitch, duration etc.) of the sounds rather than any inherent meaning that you previously might have given them.

Helpful Hint 3: Change your surroundings.

Maybe you can remember a time when you were on holiday, perhaps somewhere abroad, somewhere you’d never been before. Maybe you can remember noticing how different everything was? Maybe the different shaped and coloured houses from the ones in your own country? Maybe the different landscapes and scenery? Maybe the different cars, buses and trains? Even the sounds, smells, and taste of the food may have been different?

Often, for the people who have lived there for many years, the sights, sounds and smells will be all too familiar and they will have stopped noticing them – they will just have become part of the background to their lives. The same can happen to us when we become so used to the things around us that we no longer take interest in them, and they become humdrum, and no longer warrant our attention.

Through changing our surroundings, even if only temporarily, we can learn to reawaken to our external environment, to consciously notice the things around us, and to take an interest in them again. Then, when we return to more familiar surroundings we may find that we notice things that we had never really noticed before.

Whilst developing mindfulness of our surroundings maybe a great excuse to take a holiday it’s not absolutely necessary! We can change our surroundings in so many ways. We can visit new places in our locality, we can redecorate our houses, and dare I say we can even change where we work!

Helpful Hint 3 ½: Change perspective on your surroundings.

This is an additional ‘half a hint’ as it’s related to the previous one!

Often it is difficult to permanently change some of our surroundings, at least in the short term e.g. where we live or work. It’s always possible, however, to change the perspective we take on our surroundings.

Recently I had the pleasure of doing a tandem paraglide flight over lake Annecy in France whilst I was there on holiday. I’d already been camping in the area for two weeks and I’d visited the area last year, including climbing many of the surrounding mountains, so I was relatively familiar with it. The unique ‘birds eye’ perspective that the paraglide flight gave me, however, completely transformed the way I viewed my surroundings, and it was a very rich and engaging sensory experience – especially the take-off!

I’m not suggesting that in order to change your perspective on your surroundings you need to take a paraglide flight over your home (although if you get the opportunity go for it) or even stand on a chair in your office (especially if it’s of the swivel variety!). On a practical level simply changing where you sit at work, altering the route you take to work, or even just moving some furniture around can help enormously in freshening up your experience of your surroundings, reengaging your senses, and invigorating the qualities of curiosity, intrigue and playfulness that are such an important element of mindfulness.

Hopefully the hints given above prove useful to you in developing a greater sense of mindfulness of your surroundings. In doing so we can develop a healthy ‘breadth’ to our awareness which serves to balance the inner ‘depth’ of awareness that often comes from focused meditation. In the language of Breathworks, by developing a breadth as well as a depth to our mindfulness practice we can become ‘bigger containers’, and as a result we are less susceptible to being swayed by the inevitable ups and downs of daily life.

Finding Your Why – How Mindfulness Can Help

By Christopher Joseph

Many of us now live what are often very busy lives in the frantic world we now find ourselves in, and as such we are often subject to constant distractions. As T. S. Eliot put it: we are “Distracted from distraction by distraction”.

Our attention can often feel pulled in many different directions as a result of living lives in the ‘fast lane’, and as such we can often lose sight of our why – why we’re actually doing the thing we’re doing!

But why is knowing ‘our why’ important?

When we are in touch with our reasons for doing something we have clarity of purpose, and there is greater alignment between our actions and our values, and as such we often feel less internal conflict, we are far more at ease and our energy and motivation for living can increase significantly. This doesn’t necessarily mean that we become less busy, but it does mean that we usually expend less energy since we are swimming with the flow rather than against it.

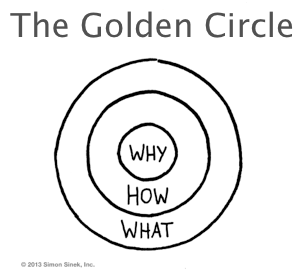

Simon Sinek in his TED  talk ‘Start With Why’ and in his book of the same title talks about the ‘Why, How, What’ golden circle (see picture). He talks about how companies and organisations often get lost in focusing on ‘What’ they do and sometimes ‘How’ they do it and as a result lose touch with the actual reason for being in business in the first place – i.e. their ‘Why’. He highlights the fact that most companies work from the outside in rather than starting with their why and working from the inside out.

talk ‘Start With Why’ and in his book of the same title talks about the ‘Why, How, What’ golden circle (see picture). He talks about how companies and organisations often get lost in focusing on ‘What’ they do and sometimes ‘How’ they do it and as a result lose touch with the actual reason for being in business in the first place – i.e. their ‘Why’. He highlights the fact that most companies work from the outside in rather than starting with their why and working from the inside out.

Whilst Simon presents the golden circle model primarily in respect to companies and organisations, it equally applies, in my opinion, to us as individuals in respect to the things we do. When undertaking any new venture in life I believe it’s important that we start with our why.

The mission statement of Breathworks, in its succinct form, is to relieve mental and physical suffering in this world. This is also my reason, my ‘Why’, for doing the work that I do.

It might sound a little grandiose but I have no illusions about suddenly waving a magic wand and solving the world’s ills! However, in beginning any one to one session, group course or entering any workplace to teach mindfulness I try and remember why I’m doing it – to help people develop their own mindfulness skills so that they can live their lives with more ease and less suffering.

Wherever possible I always try and start with my why, and when I forget it, as I invariable do sometimes, and get caught in the detail of ‘What’ I’m teaching or ‘How’ I’m teaching it, I try and return to the centre of my circle, as Simon Sinek portrays it.

So what is your ‘Why’?

This is a common question that often comes up in coaching sessions, and it can be a difficult one for people to answer. When we’re busy, and have little time to reflect, we can so easily lose touch with our why, with our original motivation for doing things.

We may forget that we may be doing the job that we’re doing to support our family, or we may forget that the volunteer work that we may be doing is to support and improve our community. We may forget that the personal exercise we undertake, sometimes begrudgingly, is to support ourselves physically, and we may forget that the purpose of our meditation practice is to support and nourish ourselves mentally and emotionally.

So, how can mindfulness help us in finding our ‘Why’?

If we take a glass of cloudy, muddy water and allow it to be still, without agitating it further, then the sediment will settle with time and the water will gradually become clearer and clearer (see pictures). This is a useful analogy for what can happen in our own minds when we meditate. Over time we can gain increased clarity on many things including our thoughts and emotions, our life situation and useful insights into the nature of our personality and what makes us tick – ‘Why’ we do the things we do.

These insights into the personal nature of our character and the traits and habits we have are not always easy to digest of course! The fifth step of the ‘Breathworks 5-Step Process of Mindfulness’ is choice, and in my personal experience, however, in the long run it’s always better to make choices and decisions from a position of awareness than unawareness. When I meditate, and thus provide the conditions for the ‘cloud of thoughts’ in my own mind to settle, as the mud settles in the water, then I can obtain a greater clarity of mind – I can see things more clearly. As a result I’m more able to connect with the deeper driving forces within me, with my core values, with my ‘Why’.

Every time, however, I let myself become distracted from the richness of my present moment experience to ruminative thoughts about the past or worries about the future I am in effect shaking the glass, and thus muddying the water. It’s no wonder therefore that through constant busyness and distraction we lose this clarity of mind, and become increasingly out of touch with our ‘Why’s’ – our reasons for doing the things we do.

So, how often do we let the glass settle? And, how can we let it settle a little bit more?

For me, personally, the answer has been through undertaking a regular mindfulness meditation practice, and also by allocating a space for personal reflection outside of my meditation practice.

Through undertaking regular meditation over a period of time it is possible to obtain greater clarity on all aspects of our mind, including the core values that drive us. When we couple this with a space for personal reflection we can enact choice and thus hopefully make better decisions about which actions to undertake in the future. In doing so we can live a life where our actions are more in line with our core values, a life that is a little easier, a little simpler and a lot richer and more pleasurable to live.